I’ve got a new album coming out on Friday (11th November). Well, not exactly NEW. Well, not exactly an ALBUM.

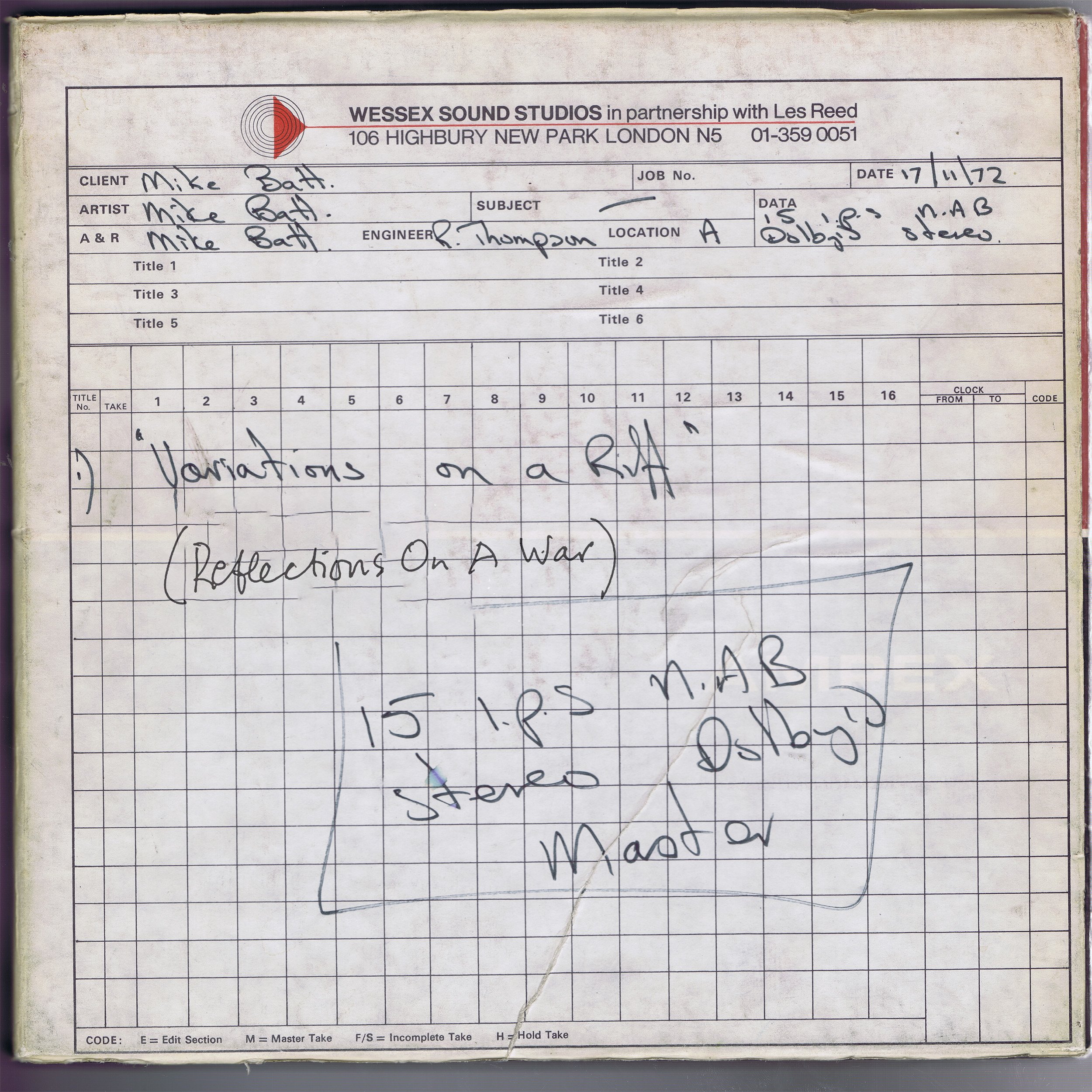

It’s 20 minutes long, and it’s EXACTLY 50 years old this month- November 2022. The date on the finished mix tape box [which we’ve used as the cover of the “new album”] is 17th Nov 1972. It’s never seen the light of day. Oddly, my “Variations” album reflected my feelings about the Vietnam war which was raging at the time. It’s sadly relevant to what is happening in Ukraine today.

Back then (as now) I did all sorts of styles of music to make a living. I wrote jingles, I made singles. I made albums by thinking up ideas (“Synthesonic Sounds was something I just made up to sell to PYE records and make enough to keep alive for a while longer]. So it was in that atmosphere that I got ambitious when a cheque for £11K landed on my doormat. It was more money than I’d ever seen. You could by a 3 bedroomed semi in a posh suburb for that. Instead of buying a house, I splashed it all on this very ambitious protest album about the Vietnam war! I could only afford to make 20 minutes of it- but I figured I could finish it once I landed a deal.

Here's the bit from my autobiography that covers this “adventure”. Ironically, everything you hear on this angry and (at the time) unusual rock album was played and written by the very same team that made all the Wombles records (Chris Spedding, Les Hurdle, Clem Cattini & Ray Cooper)

So there I was, back in the days when I had composed and recorded the Wombles and shelved the Wombles record because Decca wouldn’t let me make an album of Womble songs, then before ever selling the Wombles, started the “Big Revolt” project, bizarrely financed by performance royalties surprisingly received from unexpected American TV showings of a Yoga TV project which had once threatened to bankrupt me because of the stupidity of my own union.

Artistically, the war concept album was much more the serious “me” that wanted to say something, - write something of substance. It contained influences ranging from Bartok to Led Zeppelin, and was bold and innovative. Stylistically, it was like nothing else that had preceded it or has ever followed it. It had guitar riffs interspersed with flute and oboe lines, angry vocals sung by a friend of mine called Tony Reece, and after I had spent the 11,000 pounds recording half of it (it would have cost 22,000 pounds to record all of it) – I set about trying to get a deal for it with a record company. I decided to think big about it. I wanted to score a massive record deal that would set me up for life. I hired the most recommended US attorney, a top-dollar lawyer called Richard Roemer. US music business attorneys aren’t just lawyers, they are deal makers and relationship facilitators. I made the trip out to New York, figuring this was a US deal, not a British deal. I had never been to the States. I was 22 years old and a bit scared of New York and its violent reputation. I had asked a friend where the best hotel was in New York. He said “The Americana”. It wasn’t. It definitely wasn’t. But that’s where I stayed, and I arrived during the American Meat Institute Convention so it took me an hour to check in. Everybody had badges with “AMERICAN MEAT PACKERS CONVENTION , Hi, I’m (GEORGE, FRANK, CINDY)”

Clive Davis was just ending his days at the helm of CBS records before he got fired. I met him briefly but my meeting was with his Head Of A&R, Skip (somebody). Skip played my 20 minute tape all the way through at high volume, proclaimed it to be a masterpiece, told me he would get back to me, eagerly took my contact details and I never heard from him again. I was elated as I left his office. Apart from Skip, Dick Roemer had earned his vast fee by getting me in to see the presidents of most of the major companies, including Jack Holzman, - a charming and erudite man who ran his company, Elektra Records from his skyscraper office building high above Columbus Circle – a building which would one day be knocked down so that Donald Trump could build the very building that I sit in now, writing this account. I met with and played my album to the legendary Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, in the same building. These were great meetings for me. I had a great record, I was young, these were the top people in the business, and tough talkers who would tell me if they didn’t want to waste their time with me. All of them raved about my record. I didn’t know that I would never see any of them again for years, or ever.

My scheduled trip was to include LA as well. There, once again I had asked where the best place was to stay, and was told the “Hyatt House” on Sunset Boulevard. In those days it really was a rock ‘n’ roll hotel. On my first evening in the bar, Mark Bolan and Mickey Finn came in and we spent a couple of hours chatting and talking. I’d known Mickey from Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, and Mark, just from being around the business. Meeting-wise, I got to see all the big shots that Richard Roemer had set me up with, including Joe Smith, who ran Universal Records, some top guys at Motown, and most importantly for me, Jerry Moss, the “M” of A&M, the company he owned with his partner Herb Alpert.

Moss’s office was in Charlie Chaplin’s old dressing room, - the record company had bought Chaplin’s old studio as its base. His office reeked of success and good taste, and he was a charismatic and polite character. He must’ve been about 42 years old. He listened intently and loudly to “The Big Revolt” and then spent quite a long time raving about its uniqueness, vision, commercial appeal and artistic originality. He asked what deal I was looking for. I said I wanted a three album deal at a hundred thousand dollars a record.

It was a lot of money I was asking, but not unheard of in the States – that’s why I was there instead of England. He didn’t blink. Said the deal sounded fair and and asked time to think about it, explaining that he had a sales convention starting the next day and would be out of town; how long would I be in town? I said I had been planning on leaving the next day. He said he wouldn’t be able to let me know for sure for about three days but that it would be a quick deal to close if we were both willing, on his return. I said no problem, I’d stick around in town.

I hung by the pool on top of the Hyatt House waiting for the phone to ring. It was before mobile phones, but they had a phone they could bring you by the pool, on a cord. The New Seekers were staying in the hotel – it was the height of their short spell of fame – and I got to know them a bit, as they were in the pool all the time. After four or five days I managed to get Jerry on the phone. He was still at his convention, and would be back the following Monday, could I wait another few days? I said no problem. I went back to the pool and waited. Finally, not hearing back, I left for England and rang him from there. I had hoped we might close the deal while I was in LA. That’s how keen Jerry had seemed. When I got back, I called him. He explained that he had just acquired the rights to the orchestral version of “Tommy” by the Who, - which he saw as similar (it wasn’t) in that it combined rock attitude and instrumentation with a symphony orchestra. He didn’t feel he could take on both projects. He was sorry.

I had now exhausted all my high level contacts in the States – all of whom had raved about my innovative music and production, - and I had run out of money and into overdraft at the West Byfleet branch of the Midland Bank. Worse still, nobody wanted my record. I turned to the UK record business and in particular to Purple Records, the label run by Deep Purple, who at the time were in their prime as one of the World’s top rock bands, and sympathetic to symphonic work, since Jon Lord was their keyboard player, and he himself had classical aspirations.

I met with a man called Tony Edwards, who was one of their managers. Tony loved the record. Asked if he could keep a copy. By now, the deal I was looking for was more along “British” lines, something like 10,000 pounds, - just enough to get me out of the hole I was in and some of my costs back. A week later I called Tony and he said he was very interested indeed. We had another meeting. At that meeting he said he had played the record to Ian Gillan, Purple’s lead singer, and that Ian would be interested in replacing Tony’s vocals with his own. I swallowed and agreed. My arse was on the line, Tony the singer’s wasn’t. Tony Edwards then said that Ian Gillan also wanted to re-write my lyrics. In other words it would become Ian’s project and I would be the producer/composer. This is my recollection of the meeting, so it may not be true in every detail, but it is what Tony told me as far as I can best remember it. I thanked Tony and walked politely from his office and that was the end of the matter. I was now in deep shit financially. Instead of buying a house and giving myself some financial headroom to work on my next project, I had blown the lot on the big gamble and failed. I sent the project with a friend to try to sell it at Midem in France, but no joy. Uncomfortable calls were coming from the bank every day.

Stream/Download here - https://ada.lnk.to/Variations